Transplanted from other states or other continents, Montana's introduced upland bird species are now a welcome presence for many hunters. Here's how they arrived and where to find them.

"ON THE BOATS AND ON THE PLANES, THEY'RE COMING TO AMERICA," wrote

Neil Diamond in his 1980 hit song. Inspired by his grandparents’ escape from Russia, “America” saluted the millions who flocked to the United States in search of opportunity and freedom.

Boats and planes also transported wildlife to the New World. Of the eight species of upland game birds with hunting seasons in Montana, only half are native. Here’s how the state’s four upland imports became established and where they tend to flourish.

RING-NECKED PHEASANTS

Native to China and other parts of Asia, ring-necked pheasants were the earliest foreign upland bird species to become established in the West. Oregon successfully introduced pheasants in 1881. Among the first releases in Montana were birds brought to the Bitterroot Valley by the Butte copper baron, Marcus Daly, in the late 19th century.

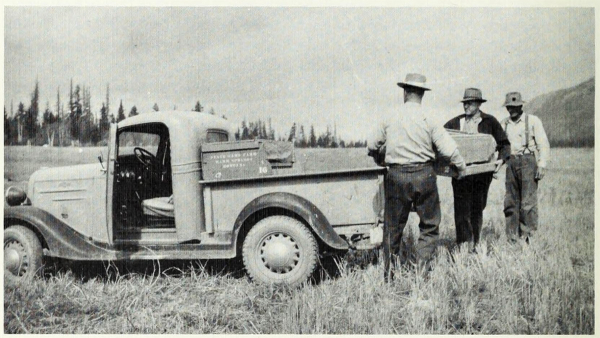

For the next several decades, private pheasant enthusiasts and the state released tens of thousands of pheasants. Every county in the state participated. A bird farm established at Warm Springs in 1929, by what was then called the Montana Fish and Game Department, rapidly expanded previous efforts. Within a few years the facility supported the annual release of around 15,000 pheasants. Three additional state bird farms in Fort Peck, Billings, and Moiese surged the yearly release count to 37,000 by 1946. One of the more innovative (but only marginally successful) production programs distributed pheasant eggs to 4-H clubs. The clubs received 50 to 75 cents for every bird reared and released.

Once the species was established across much of the state, the 1927 Montana Legislature authorized a pheasant hunting season. As the inaugural two-day season approached in November 1928, some authorities predicted that hunters would decimate the newly established population, but the harvest proved underwhelming. Season lengths and limits increased without affecting numbers. In some areas, early seasons even allowed the harvest of cocks and hens.

Today, the pheasant season begins on the second Saturday in October and extends until New Year’s Day with a daily bag limit of three male (rooster) pheasants. Like other states, Montana limits the taking of pheasants to males. The roosters’ colorful plumage makes them easy to identify, and numerous studies have shown it’s essentially impossible to diminish pheasant populations if only harvesting male birds.

By the onset of World War II, pheasants had actually become too numerous in the Billings and Hardin areas, eating so many crops that they were poisoned to lower numbers. But just a few years later, habitat loss and adverse weather severely reduced pheasant numbers statewide.

Montana is the northern limit of the pheasant’s range in North America. To survive here, the birds need three things: grain, grasslands for nesting, and winter cover (wetlands and shelterbelts). During the 1970s, numbers drastically declined as large tracts of grasslands were plowed and planted with wheat, soybeans, and barley. The additional grain was beneficial, but the destruction of nesting cover meant there were few birds to eat it.

The federal Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), which began in the late 1980s, helped restore pheasants almost to their former glory. In the program’s peak years in the early 2000s, Montana had roughly 3 million acres of CRP grasslands. Rooster numbers boomed. Montana’s annual pheasant harvest increased from an average of 84,000 birds in the years before 1985 to an average of 124,000 from 1986 to 2009.

Since then, the federal government has reduced CRP acreage in Montana and other northern states, causing pheasant numbers to drop. FWP helps landowners enroll in—and stay enrolled in—CRP through the Upland Game Bird Enhancement Program, and provides habitat management leases on non-CRP lands to help protect nesting sites and other important cover.

Spring snow storms have also hampered bird productivity in recent years, while hail in late June and early July can kill newly hatched chicks. And ongoing drought has withered much of the state’s nesting habitat. As a result, pheasant numbers have dwindled. Over the past 10 years, the yearly harvest has averaged just over 91,000 birds.

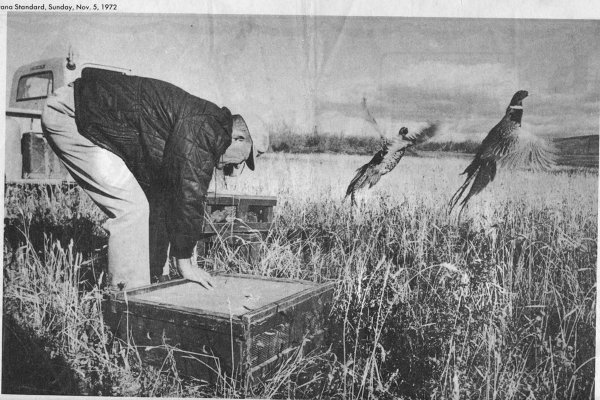

Every year since 2022, FWP has released thousands of adult pen-raised pheasants at wildlife management areas, fishing access sites, and some school trust lands around the state. Hatched and reared at the state prison in Deer Lodge, these birds are meant to provide easier hunting for youth and other beginners, with the aim of recruiting more hunters into the field.

GRAY (HUNGARIAN) PARTRIDGE

The first shipment of gray partridges purchased for release by the Montana Fish and Game Commission arrived from Europe by boat in 1923. But the birds were recorded in the state even earlier.

In 1915, a dead gray partridge was discovered in Sanders County, possibly a Canadian import. Gray partridges were released near Calgary, Alberta, in 1908. According to Arthur Cleveland Bent, a prominent ornithologist of the era, birds from the Calgary plant fanned out 400 miles across Canada in just 14 years. With the Montana border a mere 150 miles from Calgary, it’s conceivable gray partridges made their way across the border.

Native to much of Europe and Asia, the birds are also known here as Hungarian partridges, for the origins of some early imports to the United States.

Between 1923 and 1926, state game crews introduced 6,000 gray partridges from Europe. A handful of trapping and relocation efforts over the next decade further expanded the partridges’ range. Using teams of men canvassing every township, game bird surveys were conducted by the Montana Fish and Game Department in the 1940s. They concluded that the gray partridge had become the most widely distributed game bird in Montana, less than three decades after their official introduction to the state.

Like pheasants, gray partridges thrive in grain-growing regions. However, they do best in areas that are drier, have shorter grasses, and lack dense brush or cattails for winter cover. On my boyhood home west of Three Forks, my father cultivated a patchwork of wheat and barley fields interspersed with native pasture and a few hayfields. A neighbor rotated wheat crops on “strip” fields separated by brushy wind breaks. Although they didn’t hunt partridges and had no intention to do so, Dad and the neighbor created superb partridge habitat. Frequently, while I was trailing milk cows to the barn or repairing barbed wire fence, an explosive, startling flush of partridges at close range sent my heart racing.

One of the most notable characteristics of gray partridges is their remarkable reproductive efficiency. Females may lay up to 22 eggs, and when conditions allow, brood survival can top 50 percent in exceptional years, with a dozen chicks sometimes still tagging along with mom as hunting season opens September 1. Each year, Montana upland hunters harvest roughly 28,000 gray partridges.

CHUKAR PARTRIDGE

Like gray partridges, chukars were transplanted from Europe, but the birds didn’t take to Montana with the same enthusiasm. The native range of chukars includes a wide swath of Europe and Asia from the Balkans through the Middle East to northern India, China, and Mongolia. Montana’s first documented releases occurred in 1933 along the Yellowstone River near Glendive. An analysis by the American Museum of Natural History concluded that the chukars released in Montana were from a variety that originated in India.

For the next several years, managers stocked limited numbers of chukars in 16 counties in a wide range of habitats. Then in the 1950s, the state released another 5,000 birds in various habitats.

The chukar-release programs proved far less successful than those for pheasants or gray partridges. By 1970, southern Carbon County was the only place in the state where a hunter could regularly find chukars, and the same is true today. The birds are also occasionally spotted in the Bitterroot, Beaverhead, Madison, Flathead, and other valleys across the western half of the state.

Chukars thrive in steep, rocky terrain, but suffer in areas with consistent snow cover. In Montana, that limits where they can survive in what would otherwise appear to be viable habitat. They are often found in areas with lots of non-native cheatgrass, but will readily forage on alfalfa and grains when available. Fleet of foot, chukars prefer to elude danger by running uphill rather than flying like most upland birds. When they do flush, their flight is similarly explosive to that of gray partridges. Birds pinned in cover with no obvious escape route on foot sometimes hold well for pointing dogs. But in general, chukars can be maddeningly difficult to hunt, even for advanced shotgunners with seasoned dogs.

FWP hunting regulations now lump chukars in as part of an aggregated eight-bird limit with gray partridges. My wife, who loves pheasants, would disagree, but I consider the delicate white meat of a chukar to be the most delicious of all upland birds.

WILD TURKEY

Montana’s largest upland game bird is also a relative newcomer. The native range of the wild turkey historically extended only as far north as southern South Dakota. It was just too cold north of there for the birds to survive.

That is, until the widespread planting of corn, alfalfa, wheat, and other crops provided enough calories for turkeys to make it through Montana winters, and in recent years, even as far north as southern Canada.

Several attempts by private parties to release pen-raised wild turkeys failed to establish populations to the Treasure State in the 1930s. In 1954, the Montana Fish and Game Department acquired wild-trapped Merriam’s turkeys (a subspecies) from Colorado in exchange for mountain goats, and the birds were released in the Judith Mountains northeast of Lewistown. Turkeys of the eastern subspecies brought in from South Dakota were also released over the next few years around Ekalaka and Ashland. These wild birds flourished, and within a decade, some of their descendants were trapped and relocated to 19 sites around the state. In the meantime, private individuals successfully established populations of the eastern sub-species to the Flathead Valley as well.

Today wild turkeys are found in every one of Montana’s 56 counties. Concentrations are highest in the Flathead Valley, the Missouri River Breaks, and the state’s south-eastern region.

Montana’s first turkey hunting season was held in 1958. Today the state offers hunting seasons in both spring (males only) and fall (either sex).

Wild male turkeys can weigh more than 20 pounds, roughly eight times that of a rooster pheasant. Turkeys are remarkably swift of foot, but when pressed can quickly take to flight.

Wild turkeys prefer open forests and edges near agricultural crops, especially grains. In recent decades, enterprising birds have taken up residence in various communities across Montana, finding abundant feed in parks, at bird feeders, and across lawns. The more widely distributed Merriam’s variety favors ponderosa pine woodlands and riparian areas. Turkeys thrive in brushy cover with high-calorie food sources that help them maintain their body temperature and survive winter cold.

Concentrated populations of wild turkeys can be a problem for agricultural operations where the birds defecate on or eat silage, hay, and other feed stocks. In suburban areas, turkeys may befoul neighborhoods with their excrement. Toms can become aggressive toward people during the spring mating season, and they occasionally damage the finish of vehicles by attacking their own reflections in the paint. But for the most part, turkeys have integrated well with their human neighbors and other wildlife.

PRIZED IMPORTS

One of the persistent fish and wildlife management concerns when it comes to non-native creatures is their harm to endemic species. For instance, non-native American bullfrogs voraciously eat native frogs and toads, English sparrows bully native song-birds, and brook trout brought here from eastern states outcompete Montana’s native cutthroat trout.

Fortunately, according to FWP upland bird biologists, Montana’s naturalized, non-native upland birds don’t dampen the fortunes of native species. Near my home in Red Lodge, I have harvested pheasants, gray and chukar partridge, sharp-tailed grouse, and sage-grouse all within a few miles of each other. I’ve seen pheasants and sage-grouse foraging in the same field in peaceful coexistence. Ditto for sharptails and gray partridges.

Biologists tell me that’s also the case elsewhere in Montana. For reasons not fully understood, the newcomers seem to coexist well with the native birds. This fall, I’ll be back out in pursuit of these prized imports with my wife Lisa and our English setter Percy. Those birds may not be native to the state, but we don’t think Montana would be quite the same without them.

— Jack Ballard

Writer and photographer Jack Ballard lives in Red Lodge. This article originally appeared in the September-October edition of Montana Outdoors, a magazine of Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks. Click here to subscribe.