Barring a minor miracle—or a change at the top—it appears that offshore boats operating along most of our Atlantic Coast are headed for a 10 knot speed limit to protect Right Whales.

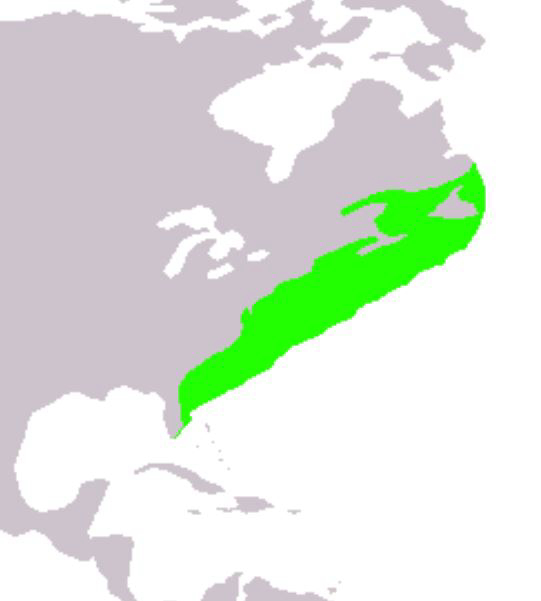

The rule — proposed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) — would restrict small boats to 10 knots (roughly 11 mph) along much of the Eastern Seaboard for multiple months out of the year, to reduce the likelihood of mortalities and serious injuries to the critically endangered right whales from vessel collisions. The proposal had been due to take place by the end of 2023, but was delayed to 2024 in November.

Whale conservation groups say there are only 356 known North Atlantic right whales still in existence, and with the perilously slow reproduction rate of the species, losing any of them causes major damage to the prospect of continued survival.

On the other hand, National Marine Manufacturers’ Association (NMMA) points out that a 10-knot speed limit would completely cripple the multi-million-dollar offshore fishing industry, making it impossible for boats to get out to most fishing grounds and back in a day.

Currently, thousands of boats ranging from outboard-powered 25-footers to 70-foot sportfishers with massive twin diesels make the run daily to areas where billfish, wahoo, dolphin and other pelagic species roam. They also chase bluefin tuna and stripers off the northern part of the U.S. coast.

The National Marine Manufacturers Association (NMMA) has expressed ‘disappointment’ with the US Department of Commerce’s decision to advance the North Atlantic right whale (NARW) Vessel Strike Reduction Rule to the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) for a final review.

“We are extremely disappointed and alarmed to see this economically catastrophic and deeply flawed rule proceed to these final stages,” says Frank Hugelmeyer, president and CEO of NMMA.

“The proposed rule is based on incorrect assumptions and questionable data, and fails to distinguish between large, ocean-crossing vessels and small recreational boats, which could not be more different from each other,” says Hugelmeyer.

NMMA argues that the proposed rule could put more than 810,000 American jobs and nearly $230bn in economic contributions in jeopardy. More than 95 per cent of boats sold in the US are made in the US, and approximately 93 per cent of boat manufacturers are small business owners. The association argues that many coastal economies are built on recreational boating, fishing trips, and the hospitality industry that require access to the ocean, and this rule would create ripple effects throughout these economies.

“The proposed rule ignores the advanced marine technologies available now that can better protect the North Atlantic right whale and prevent vessel strikes,” says Hugelmeyer. “Bottom line, the rule’s many blind spots spell dire consequences for boater safety and accessibility, the economic vitality of coastal communities and marine manufacturers, and the livelihoods of countless supporting small businesses, all while undermining years of progress in marine conservation.

The movement of the draft rule to OMB represents the last step of finalizing the rule.

While nobody wants to see even one of these whales lost to collision with a sportfishing boat or recreational yacht, it’s pretty clear that the heart of the issue lies with commercial ships transiting the area, with 40’ drafts and propellers that slice a 20’ arc or more. These giants can’t stop and can’t change directions quickly, and so if a whale gets in their way, even if it’s seen, it’s likely to be hit. A baby right whale was killed in this way earlier this spring off Georgia.

Sportfishing boats and yachts draw far less water, and are also much more maneuverable. The odds of hitting a whale are very small so long as operators are not running at night or on auto-pilot, both of which could reasonably be regulated without the impact of a blanket 10-knot rule.

In any case, it looks like the rule is rolling towards approval unless it can be halted by intervention from above. Those who enjoy these fisheries would do well to take the time to message, email and call their congressmen asap.

— Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com