In my effort to get back to my roots, I jumped on the opportunity to get a book written by one of the gun writers I recall from “the old days,” Major George C. Nonte. The book is Handgun Competition: A Comprehensive Sourcebook Covering All Aspects of Modern Competitive Pistol and Revolver Shooting (1978), from Winchester Press.

The old days weren’t all good, nor all bad.

The book examines bullseye (precision), PPC (now “Police Pistol Course,” formerly and alternatively “Practical Police Course” and other things), International (ISU), “Combat” (early IPSC), International Handgun Metallic Silhouette Association – and more. Maj. Nonte also covers gear, reloading, gunsmithing – there’s a lot of material in this old book.

He retired from the Army as a Major (Ordnance Corps, naturally) and was a prolific writer – in magazines and in books. I’ve owned his tomes Pistolsmithing, Handloading for Handgunners – and now Handgun Competition.

He passed on just under a year after I started in police work; I never met him. In fact, he passed just before the current book I’m reading was published. His final book, Combat Handguns, was published in 1980, finished by Edward C. Ezell and Lee Jurras, who assisted his son David Nonte, with the draft manuscript.

Why look back at an old book on what many would consider prehistoric competition shooting?

It seems to me that learning where we were, soaking up some of the lessons learned, can help me with my shooting and help explain the process to those who follow.

More than just a trip down memory lane, it provides bits of useful advice for handgun shooting. Like the good Major, for years I questioned the practicality of traditional handgun target shooting as preparation for battle – or as a precursor to success in combat.

While people will (appropriately) note that many of the 70% of possible qualification shooters in police and military service have survived lethal combat, I’m not sure that’s the point. The element of chance in winning – or just surviving – gunfights is always in play.

The people who seem to have faced this threat successfully many times will tell you that competition did prepare them for the stress of battle.

It wasn’t the same – and that’s not the point.

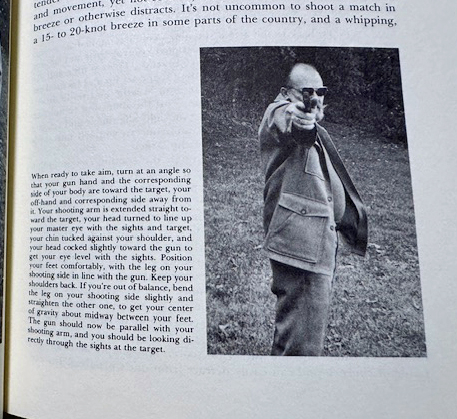

Accurate handgun shooting in competition is nearly 100% a mental effort. While people focus on the physical aspects of shooting (stance, grip, sight alignment/sight picture, trigger control, follow through), it’s having the reps to do that automatically, freeing up the brain to deal with other problems, like match jitters.

As to speed, it’s not as critical as timing. In confrontations, there’s judgement to be considered – whether to shoot, when to, when not to, is it even safe to shoot? – that takes up “executive brain” function. There’s no time to trifle with “did I get my grip right?” or other minutia.

From precision – where even rapid fire is considered these days to be “slow” – to PPC, which required a draw and reload on each string of fire – to IPSC, which in the early days was like a track & field event – time plays a role. The disagreement is over what that role is.

As Ken Hackathorn points out, in a fight you won’t need someone to tell you to shoot faster; you’ll wish someone was there to tell you to shoot better.

If you like seeing how old-timers did their own home gunsmithing and how competitors reloaded competition ammo, this book is a good resource. In some cases, it’s “don’t reinvent the wheel.” In others, it’s “Oh, that’s how they did that.”

While I’m not moving into competition – except competing with who I was yesterday – I’m finding this text informative.

— Rich Grassi