In my sudden return of interest in the “U.S. Pistol, Caliber 45, Model 1911 (and 1911A1), I’ve been watching the younger set explain how they sort their low-cost clones out, giving me the idea I should rehab a few 1911s.

One is a 1996 Clackamas Kimber Custom Classic, obtained for an article for the sadly defunct Harris Publications. After shooting it, getting images and writing pretty words, it went into a safe and that was that.

It’s a good one to settle up before it moves on.

The only serious change anyone would notice is that the full-length guide rod and hole-in-the-center spring plug that went into a plastic bag for the new caretaker.

I replaced that with a Wilson Combat #566 recoil spring plug (ringed cap), their #575S recoil spring guide spring guide, and the Wilson Combat 10G16 recoil spring for 5” 1911, 16-pound.

Why a 16-pound recoil spring? I thought about that one for a while. In my day, we routinely changed factory recoil springs to 18- or 20- pounds. It was the 1970s and lots of us didn’t know what we didn’t know.

Larry Vickers mentioned that in his FTA podcast some years back. Delta took a rack-grade 1911A1, a Delta tuned-and-updated 1911A1, the HK USP 45 ACP and the GLOCK 21 to a desert training site and used the guns like the Unit people had to use them: open-top holsters (“leg” rigs in those days, though the plate-carrier rig of today would likely be the same), fast-roping off helos in the fine dust/sand environments in which they worked.

The gun that tied up first, as I recall, was the G21. Particulate material came in through the open discharge vent at the rear of the gun at the base, locking the striker up solid. This was followed, surprisingly, by the loose rack-grade 1911. The custom 1911 did better and the USP had no issues.

Why?

Environment. If the gun is carried in conditions of desert surfaces and rotor-wash, the guns will get inundated with fine sand/dust – which prevents function. The problem of the rack-grade GI, with its 16-pound recoil spring, was failure to go into battery. The Delta guns had 18-pound recoil springs.

So why am I going with the original spec for five-inch steel 1911s in 45 ACP? Because that’s the original specification and it worked from 1911 through to the GWOT.

If I wear that cannon, it’ll be worn under a cover garment. I won’t be doing dynamic entries into the kill-zone, I’ll be looking for a way to avoid it. I may have up to 22 rounds of hardball-equivalent in overall-length and bullet profile – that’s not enough shooting to tie up the gun even if I use all the ammo.

The idea behind the heavier springs as I heard it back then was to reduce the impact of the slide opening and running back … you know, recoil.

The primary function of the recoil spring is to return the slide to battery; that requires lubrication and not a ½ pound of sand. The spring that reduces, slows and stops rearward movement of the slide is the main spring.

Sometimes referred to as the “hammer spring,” it has pressure against the hammer, transmitted via the hammer strut. That’s what reduces the speed of the recoiling slide – a good, original-spec 23-pound mainspring.

That’s what I had intended for the Kimber Custom Classic.

After changing to the standard recoil spring system – and with the significantly longer new recoil spring – I went to test fire the old Kimber.

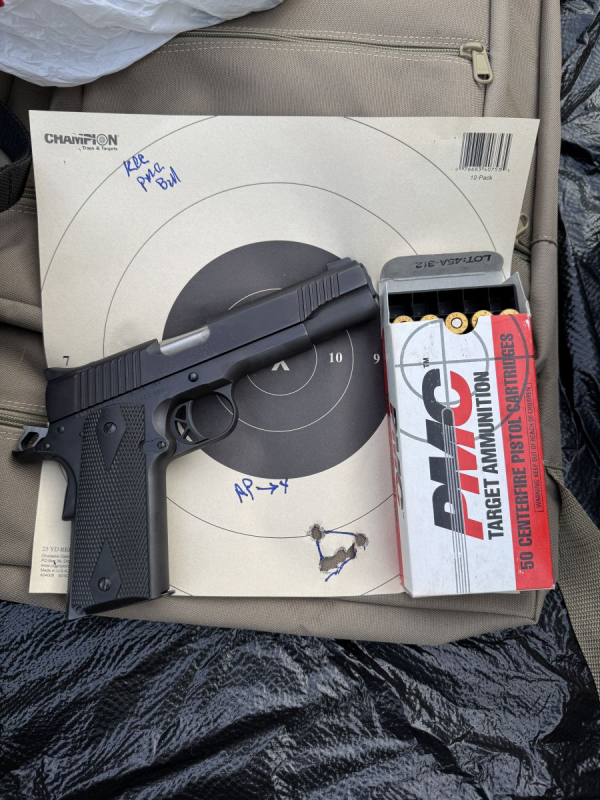

Taking the Wilson-ized 1996 Kimber Custom Classic to the range, I used PMC 230 grain FMJ to check zero. At 20 yards, using the RansomMulti-cal. Rest atop a Manfrotto tripod, I shot a 7/8” group (a fluke). Using the six o’clock hold, the group was at the base of the B-8 repair center.

Using more-or-less ball-equivalent profile Federal 230 grain HydraShok HP ammo, I shot the old Kimber using a KimPro “Tac Mag” and a “Kimber-“ marked stainless magazine. There were no stoppages with either.

The old gun is now boxed with the original spring, guide-rod and plug, with the two extra Kimber magazines. That new recoil spring is just what the doctor ordered; the gun felt solid in recoil and function. The shooter is much slower these days, but it’s good to feel the push of recoil instead of the “snap” with higher-pressure cartridges.

I carried the old Kimber Custom Classic around that day in a Galco Avenger belt holster, loaded from one of the same boxes of Federal Hydrashok that I’d shot at the range. It was strangely comforting feeling the steel, five-inch 45 on my hip.

I ended up wearing the gun home in that holster under a fishing shirt. I guess I’m still a fan of the old gun.

— Rich Grassi