|

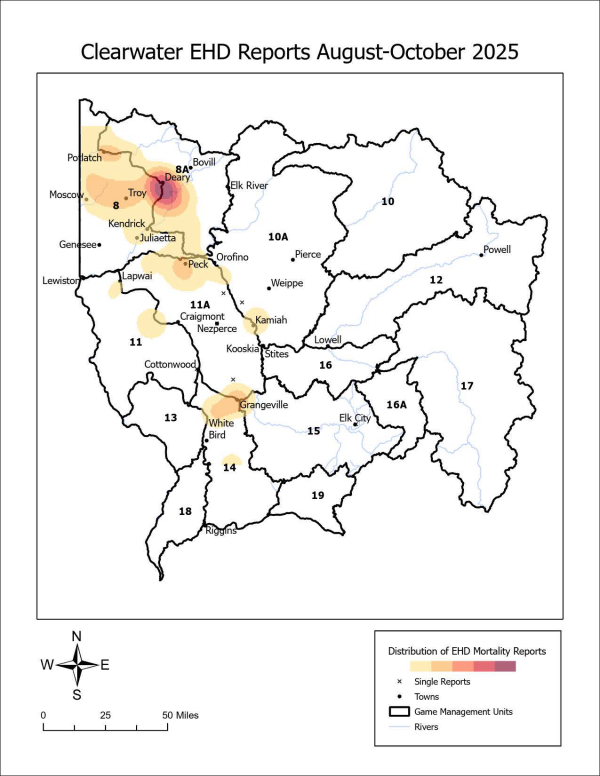

Most of the reports have come from Units 8 and 8A, with the largest concentration around Deary area

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) is not a threat to humans or livestock, but it can be alarming to hunters and landowners who encounter sick or dead deer. Fish and Game has received many questions about the outbreak, what it means for hunting this year, and what to expect for the future of white-tailed deer populations in the Clearwater Region.

As of October 6, biologists have received ongoing reports of just under 1,000 white-tailed deer mortalities in the Clearwater Region suspected to be caused by EHD. About 72% of these reports have come from Units 8 and 8A and approximately 18% have come from Units 11A and 14. In other units only a handful of suspected cases have been reported.

Estimating the actual number of deer lost during an EHD outbreak is extremely difficult. However, based on the number of reports, the 2025 outbreak appears similar in severity to the 2021 event, though centered in a different part of the region. In 2021, cases were concentrated in Unit 11A near Kamiah and Kooskia, as well as in Units 8A, 10A, 15, and 16 at lower elevations extending downstream toward Orofino and up the South Fork of the Clearwater. In contrast, most reports in 2025 have come from farther north, primarily in Units 8 and 8A, with the area around Deary being the hardest areas hit.

Impact on Hunting This Season

Despite the ongoing outbreak, Fish and Game has not recommended altering current deer seasons. White-tailed deer populations in the Clearwater Region remain strong overall, and while EHD has caused localized losses, deer numbers across much of the region remain robust and well above conservation concern.

Outbreaks of EHD are often most severe in areas where deer are more concentrated. As deer densities increase, herds become more susceptible to larger die-offs, as seen during the 2021 outbreak centered in Kamiah, and again in this current outbreak centered near Deary. Prior to this year’s event, Units 8 and 8A supported some of the highest white-tailed deer densities in the Clearwater Region.

Hunters should be aware that in some areas they may encounter fewer deer than in past years. These localized declines can be disappointing, but other parts of the region have seen little or no impact from EHD, particularly at higher elevations, and these will continue to provide good hunting opportunity. After the severe outbreaks of 2003, and 2021, hunters did not see a drop in harvest success, and white-tailed deer populations are recovering well since 2021, though not back to previous levels.

Long-Term Outlook for Whitetails

While EHD outbreaks can cause sudden and visible losses in localized areas, white-tailed deer populations are well adapted to recover from these events. Whitetails have a high reproductive capacity, with does in the Clearwater Region often producing twins. This allows populations to rebound relatively quickly after a disease outbreak like this one.

Based on experience with past outbreaks in Idaho and neighboring states, recovery typically occurs within three to five years, depending on habitat conditions and winter survival.

Fish and Game will continue to closely monitor harvest results and field observations this fall. Information collected from hunters, check stations, and landowners will help us evaluate the impact of the outbreak and ensure future seasons remain sustainable.

Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) is a naturally occurring viral disease that affects white-tailed deer and other deer species. It is transmitted by biting midges (no-seeums), which are most active during late summer and early fall. Infected deer often die within a few days, and outbreaks can cause noticeable numbers of deer deaths across local areas, particularly when deer densities are high.