|

Maryland Big Tree Program inspired national effort and continues to recognize Maryland trees

A hundred years ago, Maryland residents across the state set out to find big trees.

In what newspapers simply called the “Tree Contest,” the Maryland Department of Forestry and the Maryland Forestry Association solicited submissions of trees that were notable for their “size, history, or other distinguishing characteristics.” They asked Marylanders to mail in the record of the tree, a photo if they had one, and directions on how to find it.

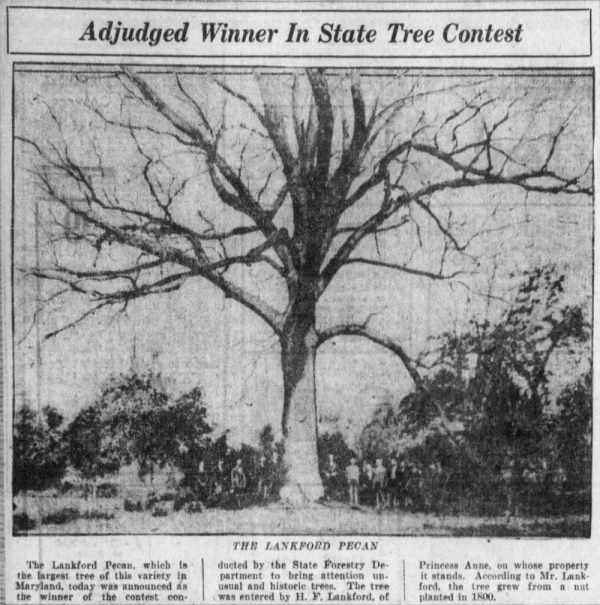

The contest, which ran from April to July 1925—with an extended deadline due to sustained interest, drew 450 entries from every Maryland county but one. A 124-foot-tall pecan tree in Princess Anne placed first, netting its owner a $25 prize.

For John Bennett, the effects of that contest live on 100 years later in the Maryland Big Tree Program, which he co-chairs, and in the nationwide effort it helped inspire as well as the excitement for forestry it generated. Bennett said Maryland’s big trees help spread awareness for sustainable forestry—adaptive management techniques that promote the long-term health of forests, allowing both big trees and full forests to thrive.

“The main thing is to continue to have publicity toward the ultimate goal of sustainable forestry in Maryland,” Bennett said. “If people buy into the fact that trees are good, people will buy into the need to support sustainable forestry.”

The Maryland Big Tree Program continues to accept submissions for large trees and has catalogued thousands of notable trees in the state. Long part of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the program now operates as a volunteer group with DNR support.

Fred Besley, Maryland’s first state forester, had spearheaded the idea for a big tree champion contest to spur interest in Maryland’s trees and compile a list of the notable trees of the state. He himself was struck by Maryland’s rich forests and spent his 36 years as state forester spreading that appreciation.

“Trees are the outstanding feature of the Maryland landscape,” Besley wrote in a 1956 booklet, reflecting on the 1925 contest. “We recognize in them the highest type in the plant world. They are the largest and oldest of living things.”

To judge the trees, Besley had devised a formula that would grade trees numerically, taking into account their circumference, height, and the average spread of their crown. Besley went around the state himself measuring trees for the contest.

The contest excluded some well-known trees, such as the Wye Oak, but helped to generate a list of trees from more than 57 species. Newspapers at the time fervently covered the contest and its entrants, including the stories of some notable trees. One white oak in Frederick County was known as the “Reno oak” because Maj.-Gen. Jesse Lee Reno, a Union army officer, reportedly died beneath it after the Battle of South Mountain during the Civil War.

“The Big Tree Contest did not end the interest in big trees in Maryland,” Besley wrote. “Rather it presented a challenge to citizens to find bigger specimens.”

Maryland published an updated list in 1937, and shortly after—inspired by Maryland’s program and using Besley’s measurement system—the American Forestry Association started a national big tree contest in its magazine “American Forests.”

Besley wrote proudly that Maryland “led by far all the states in the number of champion trees” in the first national counts, in 1940 and 1955.

The National Champion Tree Program continues today, now through the University of Tennessee, and Maryland had 15 national champions in the 2024 register, including a Kentucky coffeetree in Montgomery County and a devil’s walking stick in Baltimore County.

The Maryland Big Tree Program keeps a register of state champions and other significant trees, including a list of “GOAT trees” that commemorates significant trunks of past and present. The program also tracks some non-native trees that are not currently tallied nationally, such as what is likely the world’s largest known English elm in Gaithersburg (possibly planted in the 1770s) and America’s largest tree of heaven in Annapolis.

The Maryland Big Tree Program hosted a reunion this April to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the big tree list, and the program and the Maryland Forest Service are considering other ways to commemorate the anniversary, possibly with another public contest.

“We are excited to carry on the vision of Maryland’s first state forester, Fred Besley, in tapping people’s interest in and enthusiasm for Maryland’s biggest trees, and offering opportunities for further understanding of all of the benefits that trees and forests bring to the state,” Maryland’s current State Forester Anne Hairston-Strang, the director of the Maryland Forest Service, said.

Volunteers with the Big Tree program will still go out on site to measure big trees, and Bennett said it’s always moving to see the pride people have in trees, which are sometimes in their backyard, and may have been the sites of tree forts or wedding photos.

Joli McCathran, co-chair of the Big Tree Program, said there are two informal rules for encounters with champion trees.

“When you get to a champion tree you have to touch it—you can’t just look at it,” she said. “Then you have to think about what it’s seen. I’m just fascinated by what’s happened in the life of that tree. And anytime I’m in the forest, it’s a happy time.”

The Maryland Big Tree Program accepts nominations for big trees through its website. Bennett’s booklet on the greatest of all time Maryland trees is available by email.