With the various announcements in today’s news section formalizing the breakup of Remington, it’s time to start looking for clues as to the cause of the failure of a major company in our industry. Chalking it up to “bad management” or “poor decision making” doesn’t really do it justice. Remington, a player for two centuries, deserves more than today’s typical four sentence obituary.

Perusing a portion of the approximately 3,000 pages of documents remaining to be browsed, I was struck by the starkness of the business realities explained in Remington’s “Demonstratives” filing.

Demonstratives are essentially “show and tell” documents used in court when images are best used to convey facts. They’re essentially the use of psychology and artistic principles to communicate information. They prove that, in complicated legal cases, a picture really can be worth a thousand words.

These demonstratives had two goals: 1) Explain “why”the bankruptcy and, 2) prove that the company expended its best efforts to liquidate their remaining assets for the most money possible to the court and creditors.

These are eye-opening. And proved what the industry “whispers” had been saying for some time: Remington had been in the process of failing for a long time. Only the sheer size of the company kept it going as long as it did.

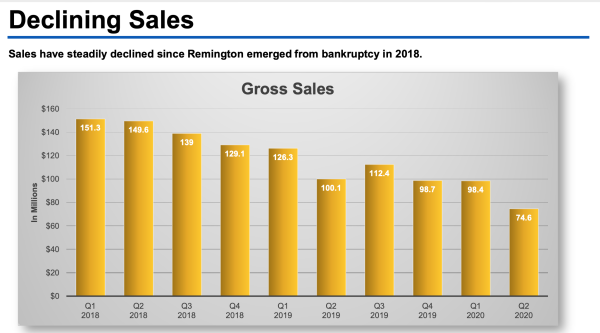

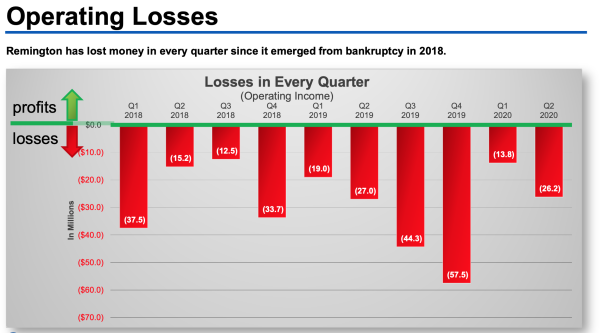

Since emerging from bankruptcy in 2018, Remington lost money in every operating quarter. A total of $286.7 million dollars over the ten quarters since Q1 of 2018.

In all but one of those ten quarters, sales dropped. From $151.3 million of gross sales in Q1 of 2018, Remington’s latest reported quarter, Q2/2020, sales dropped by more than half, to $74.6 million.

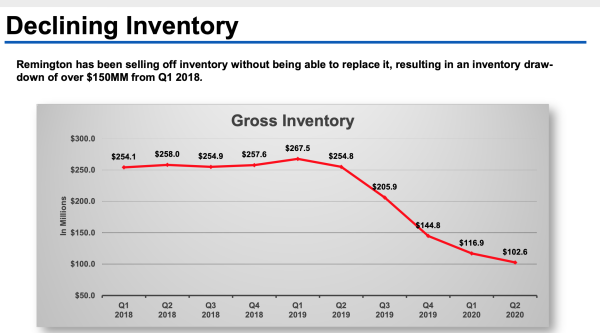

In an effort to stay afloat, Remington tried offsetting the losses by drawing down inventories, essentially selling products without replacing them or the raw materials to make more.

Across those ten quarters since 2018, inventories dropped from $254.1million to $102.6 million in Q2/2020.

You may have seen the same thing on a considerably smaller scale when shopping.

A store you frequent appears to have emptier-than-normal shelves and racks, limited selections and fewer sizes to choose from. If they’re not selling down to replenish stock for seasonal demand, they’re in trouble. Sometimes the gamble works. Most often, it doesn’t.

Remington, despite the current industry-wide boom, was simply too far underwater to climb out.

If you can’t meet demand in a boom, you’re headed for bust.

When you are talking dollars in millions rather than thousands, the terminology becomes more sophisticated, but that foundational truth doesn’t change.

A manufacturer lacking the materials needed to make product will fail.

Now, a 200-year old company, despite $173 million dollars in sales the first six months of 2020 is gone, with its parts and pieces sold to the highest bidders.

Collectively, those assorted parts-and-pieces will net $156.3 million- slightly more than the best quarter of gross sales in 2018.

But diving a little deeper into the demonstratives, you could actually make a case that the Remington team did a good job with the auction.

The original stalking horse bid was $65 million. Through negotiations with potential suitors, the bid totals rose steadily from there, ultimately arriving at what appears to be the final $159.2 auction price (before fees).

Those increases were realized via what Remington calls a “thorough and diligent auction.” A process that required Remington’s negotiations team to hold 102 meetings with “bidders and consultation parties” discussing everything from purchase negotiations to soliciting input.

Reading their meeting summary, you’ll notice plenty of industry names: Vista, Vista/Albion, SIG SAUER, Ruger, Century Arms, Hornady, Beretta, along with several “alphabet companies” all expressing interest in the various parts and pieces.

The negotiations teams used those talks to push the dollar values upwards, sometimes significantly.

In the case of Vista Outdoor’s winning bid versus SIG SAUER’s backup bid, the difference was $16.4 million dollars ($81.4 million v. $65 million).

Ruger’s successful bid for Marlin is $10 million dollars more than Long Range Acquisition’s backup.

Taking the long view, however, the results aren’t so positive. Looking at the results of bidding for formerly successful companies now considered “non-Core assets” you realize just how badly some companies brought under the Remington umbrella fared.

The “Core” assets, Remington’s ammunition and firearms, Barnes Bullets, and Marlin, accounted for $154.9 million of the auction.

Those “Non-core” assets which include DPMS, H&R, Stormlake, AAC, Bushmaster, Tapco and Parker brands, collectively, realized only $4.3 million.

Without belaboring the point, that’s considerably less than the original acquisition price for several of the individual brands now included in the “non-Core” group. Their acquirers are basically acquiring brands, not functioning businesses. H&R, for example, ceased production in early 2015. Tapco was shut down earlier this year.

With the auction finalized, we will now turn our attention to the various acquirers to get answers to the questions we’re all asking:

When -and where- will the “Core” companies resume making product under their new ownership?

What are the plans for those “non-Core” brands? Will they come back to life?

Those are questions we’d all like to see those questions answered.

We’ll keep you posted.

— Jim Shepherd