Some coastal anglers are starting to get grumpy about the growing number of sharks prowling both nearshore and offshore reefs these days. In some areas it’s getting so bad that charter skippers say the sharks view the arrival of their boats as a dinner bell, and swarm from all directions when they hear a boat pull up over a reef.

Some even say that the sharks actually follow their boats when they move from place to place at anything less than on-plane speeds. Landing more than the head of a grouper or snapper quickly becomes problematic with the big-eaters around.

Not only that, but with the tight reef fish regulations these days, it’s common to catch several undersized fish for every keeper on both grouper and snapper species. For any that make it to the boat to be released, sharks view the released fish as a living chum line. Few of them make it safely back to bottom, even with release devices like the Seaqualizer getting them quickly back to the depths.

This presents not only the obvious problem of disgruntled fishermen, but also waste of a highly-valued resource. If anglers wind up hooking 10 red snappers and sharks eat nine of them, on a broad scale this quickly impacts numbers of catchable-sized red snappers.

While the shark-killed fish are not “wasted” in an ecological sense because they feed the sharks, they are lost to human uses—and will also wind up eventually impacting the perceived number of snapper out there when NOAA Fisheries makes harvest rules for sport and commercial fishers. The seasons get shorter, the bag limits lower. And the sharks get fatter.

All species of sharks are slow-growing and slow to multiply, and they are an important part of nature’s web. But taking some steps to control their numbers a bit more tightly in some areas may be necessary to balance the scales.

It’s possible to have healthy shark populations and also have outstanding numbers of reef fish, but it’s hard to have huge numbers of both. Nature is an ever-rebalancing equation. More predators mean less prey, whether we’re talking sharks and reef fish or wolves and elk. When prey numbers get low enough, predator numbers rapidly fall, which then allows the prey to rebuild, and so on.

Man puts his finger on the scale in favor of one or the other because it has fallen to us to try to manage and preserve what nature gives us—and because we want to use the resources as well.

While we want plenty of sharks in a healthy ecosystem, we don’t want so many that we can’t make use of the resource too.

Some avid conservationists would have it that man has no place in Nature anyway, and so we should give it to the wolves and to the sharks. But we respectfully disagree.

Man has evolved as one of the predators of animal life, and we have a place in the natural evolved order of life which includes preying on other species, as nearly every living thing does.

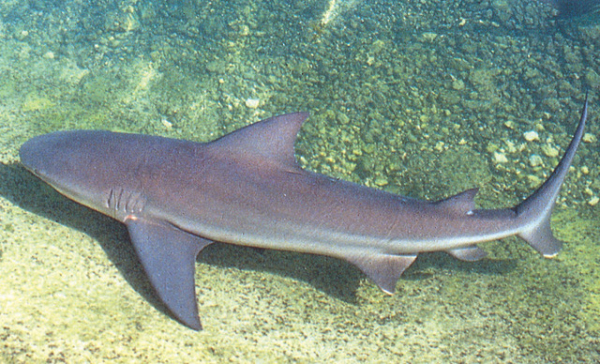

It would make sense for NMFS to up the quota on the types of abundant sharks that are eating the most reef fish—which would be bulls, blacktips, spinner and sharpnose and the like, and maintain protection of less common sharks like the great hammerhead, sand tiger, mako and white. This makes the shark fishers happy, the reef fishers happy, and balances our use of the resource.

Federal biologists are understandably conservative in their management of sharks because of the slow reproductive potential of the various species—unlike the bony fishes, they do not lay millions of eggs each year, but instead have only a few live young in most cases. So it doesn’t take a lot of harvest to have a major impact on numbers.

Worldwide studies on sharks indicate drastic population declines in the oceans elsewhere in the world, in large part due to the ridiculous practice of “finning” sharks. This feeds an unsustainable demand for one small part of these creatures, which is sold to the Orient for prices of $500 a pound—the live sharks are usually dumped back into the sea to die a slow death. The practice has long been illegal in waters controlled by the U.S.

But limited harvest of sharks—with the total catch made into leather, cartilage capsules, pet food and other useful products, would be a good thing for both fishers and fish. Hopefully NMFS will see its way to a review of the harvest in the near future.

— Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com