For that instant when the dogs lock up, just before birds flush, time stands still.

Aching joints relax, tired muscles tense, vision narrows. Lesser essential senses diminish.

It’s that too-brief time when age doesn’t matter.

Thought and action boil down to a simple mantra: Breathe. Swing. Squeeze.

If done correctly, instant gratification comes in a puff of feathers followed by the rush of retrievers. That’s followed by a lasting satisfaction that comes from knowing you’ve accomplished something other hunters have attempted since time began: putting food on the table.

I don’t hunt much anymore. Sitting up in a stand or in a blind, hoping something wanders by doesn’t motivate much unless I have a camera at hand.

But wingshooting, that’s something else.

This week, I’ve been in Kansas, enjoying an invitation extended by Chris Hodgdon. It was accepted three years ago and much anticipated. It would be “the trip” for the year. But “the trip” got delayed - twice.

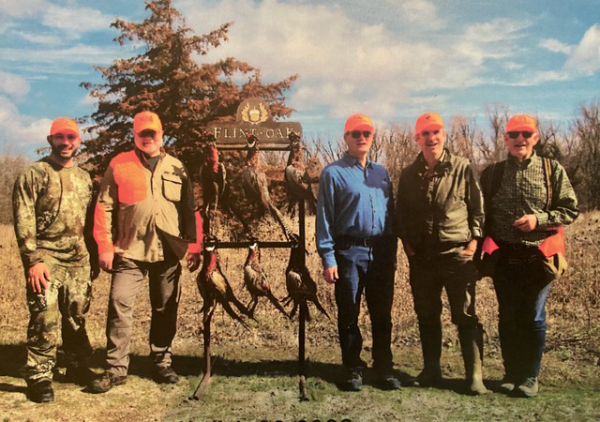

Fits and starts of life prevented my being in the windswept fields of Flint Oak outside Fall River, Kansas until this week. But it was a promise made to a friend -and myself -that I absolutely had to keep.

Standing in a damp, windy field watching hunting dogs cast about for hunkered down birds, I remembered why. This particular type of hunting still stirs me.

Wingshooting wasn’t part of my childhood. Had it had been, I might never have left the fields of the family farm to see places I dreamed about as a child. Those Kentucky fields - with pheasants, chukar or quail in them - might have been enough.

That’s how appealing wingshooting is to me.

In my youth, shotguns and birds had nothing to do with each other.

My shotgun was an “experienced” single-shot .410. And I wasn’t a great hunter or shooter with it. But powered by youthful exuberance, my well-worn .410 and I brought home more than one family dinner of squirrel or rabbit.

Walking across the fields at Flint Oak, I frequently recalled those days while quietly regretting the decades that passed between then and now when I didn’t hunt, fish or camp.

Watching the dogs search for pheasant, quail or chukar, I joked with my friends while simultaneously recalling the braying beagles of my youth as my dad, my Uncle Ollie and I hunted rabbits.

In those days, we were about as likely to “jump up” a dragon as a pheasant or chukar. Kentucky - in my youth - had been without game birds for decades. No elk herds wandered eastern Kentucky, either. A verifiable deer sighting or a decent shed antler made the local news column of the Lebanon Enterprise.

Not here. Kansas is blessed with game -and sportsmen and women who not only pursue them, but make a living welcoming others to enjoy their experiences.

Flint Oak is one of best of those places. It’s a haul from Kansas City, but worth the trip.

The three-hour (plus) drive to Flint Oak allowed sufficient time for the work I hadn’t finished to fade from memory as anticipation built. Along the way, I realized how much I needed my too-infrequent breaks.

Crossing the wind-swept fields it didn’t take much imagination to see where progressive rocker Kerry Livgren of Kansas’ found the inspiration for “Dust in the Wind” in October of 1977. The breezes gusted across the fields, raising swirling clouds of dirt that reminded me as it had Livgren, that in the scheme of things “all we are is dust in the wind.”

That was fine with me. I was content to take part of a scene that has played out many times before: hunters and dogs chasing game, each playing their part in that “circle of life.”

Honestly, my “chasing game” is an exaggeration. These days, my steps are more measured; my pace is reduced.

But the pleasure in each of those steps is heightened. The experience has become more valuable than the harvest.

Today, seeing a fellow shooter make a great shot on a fast-moving pheasant is almost as rewarding as making the shot myself.

And my frequent misses aren’t nearly so bothersome.

It’s taken me a long time to accept that not every shot will be a hit. Or realize that misses won’t be counted against me in some imaginary “life worth” scoring system.

But the realization frees me to relish that just being here. That’s my big takeaway. The cooler of fresh birds I brought home is only commemoration of the trip for my family and friends.

This too-short, twice-delayed, wingshooting trip ended far sooner than I would have liked. One more shooting session (I’d like a rematch with the “Scotty”) would have been nice, as would have another leisurely dinner with friends.

But that’s OK.

Unlike the dust in the wind, the memory of my great days afield with friends will stick in my memory. At least until it’s my time to become a small part of that dust in the wind.

It’s all part of that inevitable circle of life. Some parts are sweeter than others, but they all make the journey memorable.

Until mine ends, I’ll do my part to keep you posted. Have a great weekend.

— Jim Shepherd