|

Animal migrations and homing instincts remain one the most fascinating of natural phenomena. Salmon swim upstream and migratory birds fly south, north, and back again.

How do migratory birds know what to do? Memory is deeply implicated—molecular memory—profoundly encoded in the double helix of their DNA from eons of experience.

The first beautiful days of autumn usher migratory birds on their way before the breath of winter lays on the land: honking giant Canada geese in a V pointed south; swarms of chatty rusty blackbirds in an amorphous mass; and confusing fall warblers, singles slipping silently through sylvan stands. Birds big and little have learned a geography of survival over a span of time that rational beings can hardly comprehend.

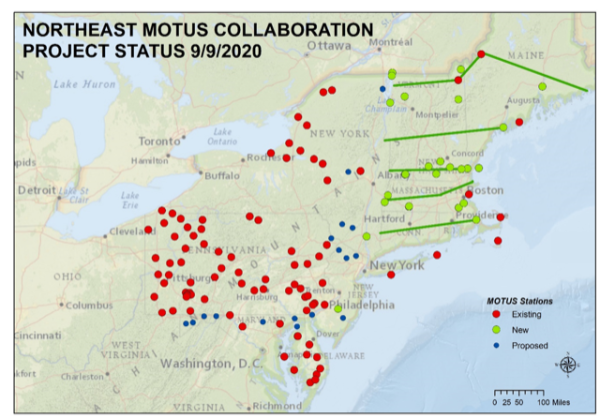

What cues birds to pick up and go, and by what routes are becoming clearer, producing big data sets from the smallest of technologies over a vast geography of the northeast United States. It’s a multistate endeavor from Maine to Maryland made possible by State Wildlife Grants administered by the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration program of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

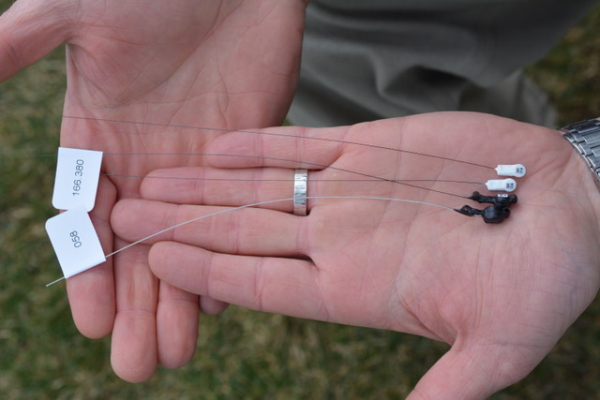

Nanotags—the size of swollen rice grains with a thin tailing antenna—attached to birds reveal much about bird habits and bird habitats. The nanotags give each bird a unique identifying number that is digitally recorded when near enough to a receiver. Their revealed flight patterns expose conservation problems that birds face in their treks north and south such as window collisions and disorientation from light pollution. Much bird migration occurs at night. The data might reveal a paucity of staging habitats—places to rest and refuel. Flying nonstop over the Gulf of Mexico is arduous.

|

Bird tagging, more commonly called “banding,” has been in use a long time. Waterfowl hunters know this. A mallard harvested in a Louisiana wildlife management area sporting a leg band might reveal that wildlife managers banded the curly tail in a Minnesota wetland two years prior. The data from that bird is only useful if retrieved post-banding by another biologist or by a hunter reporting the band. What goes unknown is where that mallard traveled between the two states. Most banded birds are rarely seen again.

Nanotags eliminate the need for biologists or citizen scientists to retrieve a tagged bird. The birds of course have to first be captured in nets, tagged, and sent on their way. Their flight data and patterns are logged via several rows of electronic receiving stations set up over a vast expanse in roughly east-west alignments. The receivers are sensitive enough to detect the passing flight of a nanotagged bird within 10 miles distant. The data are digitally recorded and stored for later analysis by biologists.

Nanotags and the multitude of receiving stations peppered across the Northeast necessitates cooperation among several entities such as conservation societies and state governments.

State Wildlife Grants support a cohesive approach to strategically placed receivers that will yield a robust, reliable data collection method useful to scientists for years to come.

Wildlife managers in the northeast are using nanotags to learn more about several bird species including rusty blackbirds and American kestrels. Nanotag data might reveal why we do not see our smallest falcon perched on wires and utility poles as much as we used to.

As the northern hemisphere wobbles back into the vernal position in the months to come, receivers placed on ridgelines and fire towers and hilltops and tall buildings in big northeast cities will be there. They will log the flight of migratory birds responding to memory to go build a nest in a woven cup or crude platform or shaded cavity in a tree somewhere between Maine and Maryland.

To learn about other conservation successes, visit Partner with a Payer.

— Craig Springer

Springer is with Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration, USFWS