If you think nature science is all Latin seriousness and spotless lab coats, you haven’t spent much time with the folks who study where Nature actually lives—in tidepools, peat bogs, and the digestive tracts of unsuspecting wildlife. Out in the field, the language of discovery is a mix of wonder, wisdom, and words that sound like the punchline to a sixth-grade joke.

Take regurgitalite.

It rolls off the tongue like something you’d challenge somebody to pronounce after their second boat ramp margarita. But the meaning is straightforward: fossilized vomit. Paleontologists coined it after some lucky researcher split a slab of shale and found a solidified splatter of half-digested fish bones—a prehistoric upchuck captured for the ages.

One of the earliest finds came from Utah’s Morrison Formation, once a Jurassic swamp full of critters with too many teeth. Something was swallowed, rejected, and immortalized. Researchers study these chunks of ancient spew to trace food webs—who ate whom, and which meals didn’t sit right.

If nothing else, it proves indigestion predates human civilization—and Pepcid--by about 150 million years.

The Bear Essentials

On the other end of nature’s conveyor belt lives the venerable term scat.

Scatology is not, as you might suspect, a new meditation trend or a TikTok wellness routine. It is, simply, the study of poop.

And yes, bears do it in the woods. Particularly Alaskan brown bears when they are consuming large numbers of salmon.

Finding said evidence can be alarming when all you’re carrying is a 9-foot fly rod, an Orvis hat, and a sense of optimism.

These piles are a treasure to wildlife biologists because each tells a story: how the salmon are running this year, which berries are ripe, and how many Orvis hats they’ve consumed recently.

It’s serious business, though, and the habit of studying droppings isn’t unique to modern wildlife folks. Paleontologists have their own specialty: coprolite, or fossilized feces.

Poop turned to rock.

There used to be a surprising amount of it scattered around Port Manatee’s spoil island in Tampa Bay. While I was busy tormenting snook with questionable casting form, my wife and kids would wander the shoreline and pick up football-sized chunks of ancient dung. We never figured out what species donated them to posterity—but whoever it was, they had been eating well.

Polished pieces of fossil poop are surprisingly attractive, resembling petrified wood. Collectors buy them proudly, proving once again that humans will spend real money on anything if you tell them it’s rare.

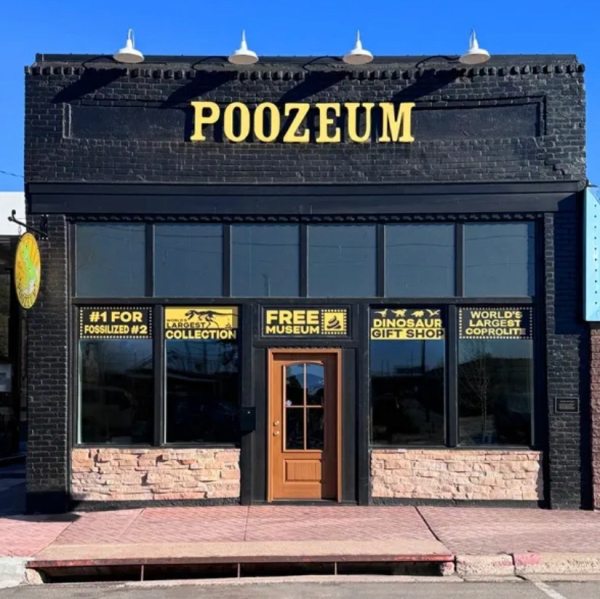

There is actually a “Poozeum” in Williams, Arizona, where they collect and sell dino dukie—and lots of it—you can see it here:

Gold of the Sea

Then comes ambergris, perhaps the most glamorous substance ever to come out of a whale’s hindquarters. Technically it’s a waxy intestinal secretion from sperm whales, the result of the indigestible beaks of the giant squid they consume. It’s nature’s version of a scented candle gone horribly wrong. In raw form, it smells like low tide mixed with a squid that lost its will to live.

But a few years drifting in the sun transforms it into something perfumers treat like treasure. It was once worth more than silver by weight, used to stabilize fragrance. The name comes from the French ambre gris, or “gray amber.” Leave it to the French to make whale gut excretion sound like a boutique cologne.

When Fish Get Fancy

Even the fish folks get their share of comic terminology. Ever hear of a myxine? That’s the family name for hagfish—the reigning slime kings of the deep. These eel-like wonders can turn a bucket of seawater into a gelatin mold in seconds. The goo is called mucin, and it’s so slick the Navy once studied it as a possible anti-fouling coating for ships. (Imagine explaining that one to Congress.) I’ve never caught a hagfish, but I’ve had some sail catfish in the boat that could probably give them a run for their money in the mucin department.

The Beauty of the Bizarre

Despite all this, there’s a purpose behind the vocabulary. Science loves precision, and if Latin helps make “owl puke” sound dignified as “pellet egestion,” so be it. Words like regurgitalite, ambergris, and coprolite may seem odd, but each helps researchers piece together the daily lives of creatures long vanished. They’re the breadcrumbs—sometimes literal—that outline evolution’s trail.

In the long, messy narrative of Earth, every burp, poop, slime glob, and fossilized hairball has a role to play. And if it gives the rest of us a chuckle along the way, that’s just nature’s way of keeping fieldwork fun.

-- Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com