Halloween is behind us, but there are still many “ghosts” lingering in lakes and rivers across the country.

Every time a crankbait snaps off in a submerged tree or a jig hangs up in the rocks, a small piece of pollution is left behind. Multiply that by millions of casts each season and it adds up to what fisheries biologists now call “ghost tackle”—the accumulation of lost fishing gear that quietly builds up beneath the surface of America’s lakes and reservoirs.

The Alabama Rig, with up to five lures on a single rig, can be particularly noxious and even dangerous to swimmers who might become entangled.

A Hidden Hazard Below the Surface

Unlike soda cans or plastic bottles, ghost tackle is easy to overlook. Most of it lies out of sight, tangled in brush or draped across rock piles. But divers and lake managers who’ve seen the lake bottoms firsthand tell a sobering story. Monofilament and braid line festoon every stump in some hard-fished lakes.

In areas of heavy fishing pressure—boat docks, riprap shorelines, and popular points—the stuff can literally be measured by the pound. “It’s amazing how much is down there,” says one Tennessee Valley Authority shoreline technician. “Every time the water drops, we see it—miles of line and piles of lures.”

Wildlife and Equipment Pay the Price

That lost tackle isn’t harmless. Stray monofilament and braid can ensnare fish, turtles, and diving birds. Cormorants, herons, and loons are frequent victims, their legs or bills wrapped so tightly that they starve or drown. Even when not lethal, the debris collects algae and becomes a chronic nuisance for both wildlife and boaters.

Anglers themselves also pay the cost. A few wraps of line around a motor prop can cut seals and let water into the lower unit, creating hundreds of dollars in damage. Hooks and lead sinkers wash up near swimming areas. Soft plastics, especially those made from non-biodegradable PVC, remain intact for decades, sometimes showing up in stomachs of fish long after they were lost.

Winter Drawdowns: The Cleanup Opportunity

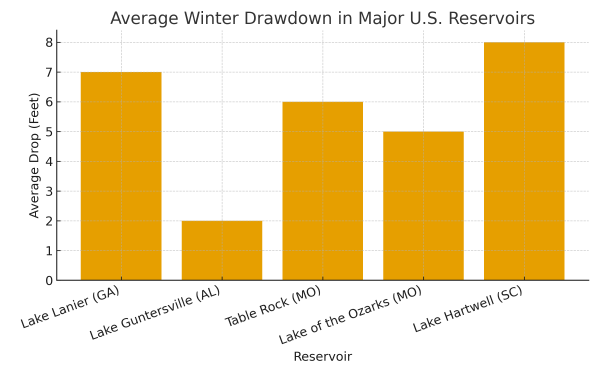

The good news is that most reservoirs in the South and Midwest are drawn down during winter to make room for spring rains—and that’s when cleanup becomes easy. When the shoreline drops, old brush piles, rock ledges, and dock pilings are exposed, revealing years’ worth of lost line and lures.

Fishing clubs and conservation groups can take advantage of these low-water months to stage “ghost tackle cleanups,” much like beach sweeps along coastal areas. It’s dirty work but rewarding, and many lake authorities will gladly provide dumpsters or pickup service for the recovered material.

Not only that but you’re likely to score a lot of still-usable high-dollar lures among the debris.

What Anglers Can Do

Individual anglers can help, too. Keep a small trash bag aboard and pick up line or lures when you see them washed ashore. Recycle old fishing line at marina drop tubes or mail-in programs offered by Berkley and others. Avoid pitching used soft plastics into the lake—stow them in a container and dispose of them properly on land.

Thinking Ahead

Ghost tackle is one of those problems created unintentionally by millions of well-meaning anglers. No single person can prevent it, but a small shift in habits across the fishing community can make a big difference.

Next time you fish a lake that’s drawn down for winter, take a walk along the exposed shoreline. You might be surprised by what you find—and by how much cleaner your favorite spot can become with just an hour’s effort and a trash bag.

As any good angler knows, a clean lake is a better place to fish—and it’s the kind of legacy we should all want to leave behind.

— Frank Sargeant

Frankmako1@gmail.com